Gender

Gender Variation and Same-Sex Relations in Precolonial Times

And what we can learn from them.

Posted July 12, 2017

[Article revised on 25 April 2020.]

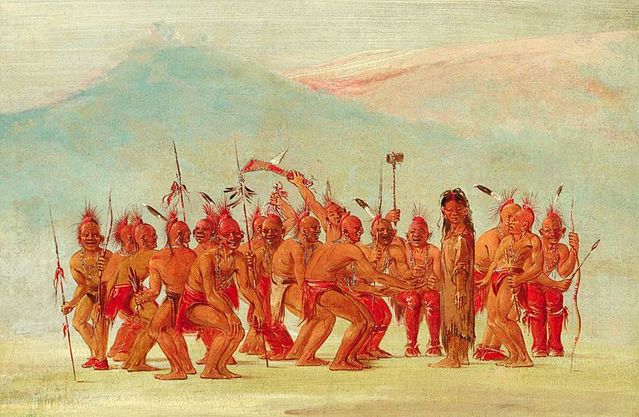

Many native American cultures, from Alaska all the way down to Patagonia, held gender variant individuals in high regard, valuing them for their unique spiritual and artistic aptitudes and important economic and social contributions.

Blessed with the spirits of both man and woman, ‘two spirits’, as they are still called, could mediate between men and women and this world and the next. They could accomplish the work of both sexes, meeting the needs of the moment and compensating for any gender imbalances in their family or tribe. They often served as educators or guardians, taking in orphans, or children from large or problem families.

Unfortunately, European colonists saw two-spirits as ‘sodomites’, and, in 1513, the conquistador Vasco Nunez de Balboa infamously fed forty of their number to his dogs.

But unlike Europeans of that time, who thought in fixed and binary terms, Native Americans understood gender as a continuum and sexuality as fluid.

Neither did they confound gender and sexuality. Two-spirits were often males who preferred males, and sometimes even married a male, but they could also be males who preferred females, females who preferred males, and females who preferred females. This did not preclude them from having sexual relations with the other gender, nor confer the status of two-spirit onto their same-sex partners.

In Samoa and the Samoan diaspora, Fa’afafine (‘in the manner of woman’) are biological males who identify as third-gender.

In most cases, boys are identified as fa’afafine from an early age, either because it is their natural inclination or because there are not enough girls in the family. To varying degrees, they take on the dress, manners, and responsibilities of a woman, although, if the need arises, they can also perform the work of a man.

Rather than being stigmatized, fa’afafine are seen as special and gifted, and valued for their work ethic and commitment to family and community.

Samoan culture does not recognize homosexuality as such: fa’afafine have sexual relations with men, although not other fa’afafine, and sometimes with women as well.

A third-gender role is also recognized in other Pacific Island cultures, with, among others, the fiafifine in Niue, the fakaleiti in Tonga, the vaka sa lewa lewa in Fiji, the whakawahine in New Zealand, the rae rae in Tahiti, and the mahu in Hawaii.

In Hawaiian culture, an aikane was a male friend of a chief, with whom he had sexual relations. Most aikanes were young males, although some were old enough to have families of their own.

Aikanes had significant clout, and, in 1779, played an important part in the killing of Captain Cook at Kealakekua Bay.

Travelling with Cook, the Welsh surgeon David Samwell reported that the aikane had for business ‘to commit the Sin of Onan [masturbation] upon the old king… it is an office that is esteemed honourable among them and they have frequently asked us on seeing a handsome young fellow if he was not an Ikany (sic.) to some of us’.

There is in Africa a commonly held belief that homosexuality is ‘un-African’, a ‘white disease’ brought over by Europeans.

But, on the contrary, European colonialists used the homosexuality that they found already in Africa as one more pretext for subjugating and christianizing the continent.

The Elizabethan traveller Andrew Battell, who lived in what is now Angola, noted that the Imbangala ‘are beastly in their living, for they have men in women’s apparel, whom they keepe among their wives’.

Battell also referred to ‘women witches … [who] use unlawfull lusts betweene themselves in mutuall filthinesse’.

The Zande of North Central Africa had a custom comparable to the pederasty of Ancient Athens: A warrior would take on a younger male lover, who, upon himself becoming a warrior, would take on a younger male lover of his own.

In the late nineteenth century, some of the male pages in the court of Mwanga II of Buganda (Uganda) converted to Christianity. Mwanga had 16 wives but when the pages began to deny him the customary sexual favours, he had them burnt at the stake.

These are but a few among countless examples of culturally sanctioned ‘homosexual’ practices in precolonial Africa.

Many traditional African languages have very old words for gender variation and same-sex relations.

More than two thousand years ago in what is now Zimbabwe, San Bushmen painted representations of sexual congress between men.

But today, homosexuality remains illegal in many African countries, in some cases punishable with life imprisonment or even death.

In 2013, President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe described homosexuals as ‘worse than pigs, goats and birds’: ‘If you take men and lock them in a house for five years and tell them to come up with two children and they fail to do that, then we will chop off their heads.’

In 2015, President Yahya Jammeh of Gambia declared: ‘If you do it [in Gambia] I will slit your throat—if you are a man and want to marry another man in this country and we catch you, no one will ever set eyes on you again, and no white person can do anything about it.’

Unfortunately, scapegoating homosexuals by speaking and legislating against them can pay dividends at the ballot box, and life for LGBT people in many parts of Africa has been going from bad to worse.

In 2015, President Obama made an impassioned plea on Kenyan soil, comparing homophobia to racial discrimination and warning President Uhuru Kenyatta that, ‘When you start treating people differently, because they’re different … freedoms begin to erode. And bad things happen.’

Kenyatta curtly replied, ‘There are some things that we must admit we don’t share.’

Our brief and incomplete survey suggests that gender variation and same-sex relations, though often driven underground, or omitted from the historical record, are timeless and universal and part and parcel of the human condition.

It also suggests that notions of gender and sexuality are, to a large extent, culturally conditioned, and that our rigid and binary concepts of male and female and heterosexual and homosexual are not necessarily the historical norm, or the best way of apprehending, supporting, and celebrating the diversity, even within a single person, of human gender and sexuality.

Neel Burton is author of For Better For Worse and other books.

References

Beaglehole, JC (1967): The Journals of Captain James Cook. Stanford University Press.

Purchas, S (1905 [1625]): Hakluytus posthumus or Purchas, his Pilgrimes, Vol. VI. James MacLehose.

Purchas, S (1613): Purchas: His pilgrims… William Stansby for Henrie Featherstone.

Politi D. (2013): Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe Vows to Behead Gays. Slate.com, 28 July 2013.

Bolton D (2015): Gambian President Yahya Jammeh threatens to ‘slit the throats’ of gay people. Independent.co.uk, 12 May 2015.

Smith, D (2015): Barack Obama tells African states to abandon anti-gay discrimination. Theguardian.com, 25 July 2015.